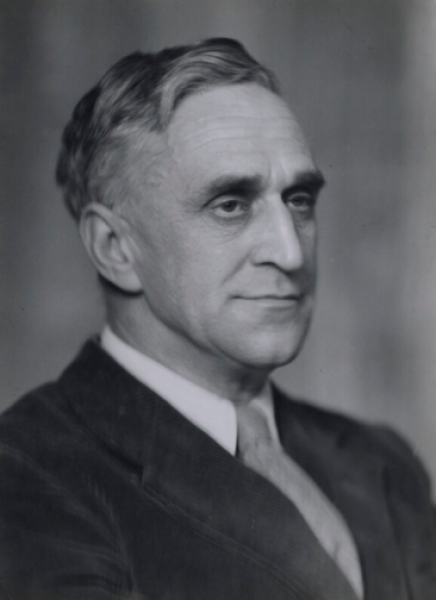

Kingsley Martin

Kingsley Martin

Born:

London, United Kingdom

Died:

Cairo, Egypt

Gender:

Occupation:

Biography

Authored By: Sean Solis

Edited By: Alex Peat, Anna Mukamal, Helen Southworth

Basil Kingsley Martin, editor of the New Statesman and Nation from 1931-1960, advocated the idea that a free press which promotes information literacy is one of the most important traits of democratic society. Martin defined liberal political media in Britain at a time when the country’s press culture faced war, censorship, and a ubiquitous conservative slant. The Hogarth Press published two of Martin’s books: The British Public and the General Strike in 1926, about the growth of the political left in Britain, and The Press the Public Wants in1947, which emphasizes the necessity of freedom of the press. Martin’s relationships with members of the Bloomsbury group such as John Maynard Keynes and Leonard Woolf helped his ideas on politics gain a foothold in British political journalism at the time. Martin’s importance to the British press is reflected in his concerns about the way that press and government are oriented to the creation of an informed society and thus electorate.

Martin was first introduced to the Hogarth Press by John Maynard Keynes, whom he met during his time at Cambridge, where Martin was a member of Magdalene College. At the time, Keynes was a fellow of King’s College; as a mentor, Martin later described him as “the most power and formidable mind I ever worked with” (Martin, Father Figures, 103). Keynes’s publications with the Hogarth Press, including The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill and The End of Laissez-Faire, reflected the Press’s wider interests in society and politics, rather than just in the literary and artistic fields. Keynes employed Martin at The Nation after Cambridge, initiating Martin’s long career in journalism. Through his relationship with Keynes, Martin became good friends with many prominent Bloomsbury figures such as Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Despite his stature as an academic and journalist, he felt a unique sympathy for the working class and a disdain for the middle-class attitudes of many of his contemporaries (Southworth 209). It was this distinct concern for the public that defined his view of the press as a bulwark against government, not as its mouthpiece, as the public perceived it to be. Martin’s connection with the Hogarth Press and the Bloomsbury group nevertheless reflected his questioning of social conventions, particularly his interest in how journalism could be useful to the public.

In 1931, when the editorship of the New Statesman became vacant, Leonard Woolf, who held considerable sway over the paper’s board, advocated for Martin to become its editor (Leventhal). When Martin took over as editor of the New Statesman, he continued the tradition that the journal “should have an ‘attitude’ to public affairs rather than a ‘policy’”. Martin himself describes his politics as that of a “dissenter” and that under his editorship, “the paper became more than anything else the voice of the minorities and the vehicle of protest” (Martin, Father Figures, 201). In the lead-up to the Second World War, the New Statesman and Martin were fiercely critical of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his policies of appeasement. Chamberlain was famously uncomfortable with criticism of the government, which he believed to be disadvantageous to a government engaged in crisis or war (Hampton, 20). To this end, Martin declared in The Press the Public Wants, “Without criticism all government degenerates into a form of tyranny, whether they are pledged to the temporal welfare of the people or to their ultimate spiritual salvation” (Martin, The Press the Public Wants, 14).

As one of the Hogarth Press’s first socio-political writers, Martin’s publishing signals a shift in the timeline of the Press. Peter Stansky writes that although “the [original] members of Bloomsbury” exemplified the petit-bourgeois middle-class, they “were nevertheless dedicated to challenging that world’s unexamined assumptions” (Stansky, 250). In his obituary for Martin, Leonard Woolf wrote, “Kingsley was lucky in finding precisely at the right age, both of himself and of Europe, the kind of paper which he was born to edit” (Woolf 1969). Martin’s journalistic style of questioning normative assumptions in Britain became a trend that reflected the wider Bloomsbury group’s commentary on the growing divergence of British social and political issues in the twentieth century.

Bibliography

Hampton, Mark. “Censors and Stereotypes: Kingsley Martin theorizes the press.” Media History 10, no. 1, 2004, pp. 17-28.

Leventhal, Fred M. “Leonard Woolf and Kingsley Martin: Creative Tension on the Left.” Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 24, no. 2, 1992, pp. 279-294.

Martin, Kingsley. The British Public and the General Strike. Hogarth Press, 1926.

Martin, Kingsley. Father Figures: The Evolution of an Editor: 1897-1931, vol I. Penguin, 1969.

Martin, Kingsley. The Press the Public Wants. Hogarth Press, 1947.

Martin, Kingsley. “7 January 1939: ‘The British people would rather go down fighting’: Democracy, rearmament and the long war.” New Statesman 144, no. 5244, January 9-15, 2015, pp. 25-26.

Simkin, John. “Kingsley Martin.” Spartacus Educational. August 2014. http://spartacus-educational.com/TUmartin.htm.

Southworth, Helen. “‘Going Over’: The Woolfs, the Hogarth Press and Working Class Voices.” Leonard and Virginia Woolf, the Hogarth Press and the Networks of Modernism, edited by Helen Southworth, Edinburgh University Press, 2012, pp. 206-233.

Stansky, Peter. On or About December 1910: Early Bloomsbury and Its Intimate World. Harvard University Press, 1996.

Woolf, Leonard. “Kingsley Martin.” The Political Quarterly 40, no. 3, 1969, pp. 241-245.