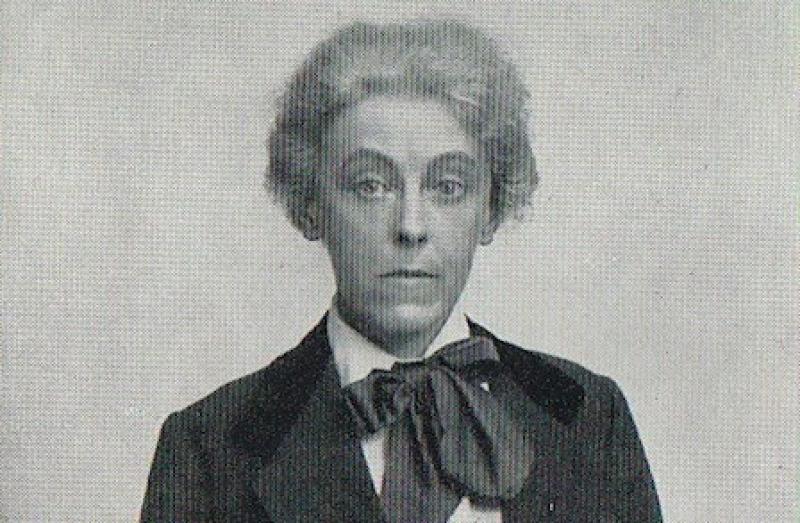

Charlotte Mew

Biography

Authored By: Bethan Tyler

Edited By: Anna Mukamal, Illusha Nokhrin

Charlotte Mary Mew (1869-1928) was a poet, fiction writer, and dramatist born in Bloomsbury, London on November 15th, 1869 to architect Frederick Mew (1833-1898) and his wife, Anna Maria Kendall (1837-1923). Mew’s childhood was altogether a happy one. It was marked by a sense of wonderment and curiosity, despite the early deaths of three of her six siblings and governed by a particularly God-fearing nurse, Elizabeth Goodman, of whom she spoke fondly.

As a child, Mew attended Gower Street School, where her over-zealous attachment to headmistress Lucy Harrison provided the first indication of her attraction to women. This attraction would present itself throughout her poetic oeuvre in the form of thinly-veiled homoeroticism, though she never formally came out and often condemned others for publicly expressing their sexualities. Mew never married or bore children, though this was allegedly due to a “fear of passing on the mental taint that was in [her] heredity” (Monro xiii), as two of her siblings, Henry Herne (1865-1901) and Freda Kendall (1879-1958), were diagnosed with schizophrenia and spent their final years in the care of mental institutions. While she preferred to keep her sexuality a private matter, Mew flouted gender expectations of dress throughout her adult life, choosing to wear exclusively masculine clothing—most notably a tweed topcoat and pork-pie hat.

Mew and her remaining sister, Caroline Frances Anne (Anne) Mew (1872-1927), with whom she was extremely close, lived together with their mother and a parrot called Willie at 9 Gordon Street, London for the majority of their lives. Here, the sisters worked on their art: Anne on furniture restoration and Charlotte on her writing. Though she is best known as a poet, Mew began her career as a fiction writer, publishing her short story “Passed” in the second volume of Elkin Mathews’s and John Lane’s literary magazine The Yellow Book in July 1894.

In the coming years, Mew would be published in a number of other notable magazines, including Temple Bar, The Egoist (“Fête”), The English Woman, and The Nation, in which she published her first poem, “Requiescat,” in 1909, and later, “The Farmer’s Bride” in 1913. The latter attracted the attention of Alida Monro, wife of Harold Monro, who claimed to have immediately memorized its verses and shared them with her husband. Harold, who had recently established his Poetry Bookshop at Theobalds Road, London, invited Mew to submit other poems that might be gathered into a book, a suggestion to which she replied with a mixture of enthusiasm and self-effacement. Alida Monro writes, “Charlotte Mew responded very kindly to the tentative suggestion, but with her characteristic lack of confidence declared that no one would want to read them if they were published” (Monro vii). Mew visited the Bookshop for the first time in November 1915, in attendance of a reading of her own poems by Alida, with whom she became close friends.

Harold Monro ultimately published Mew’s poetry in his magazine The Monthly Chapbook and in his anthology, Twentieth Century Poetry. He was also responsible for the publication of Mew’s first book of poetry, The Farmer’s Bride, in 1916. The Farmer’s Bride was expanded and reprinted—this time in the United States as well as the United Kingdom—in 1921 under the name Saturday Market. Until a posthumous volume, The Rambling Sailor, published by the Monros in 1929, the two editions of The Farmer’s Bride were to comprise Mew’s entire poetic output. Though it was small, this oeuvre earned Mew the attention of a number of prominent contemporary literary figures. Virginia Woolf asserted that Mew was “very good and interesting and unlike anyone else” (Woolf 419), and Thomas Hardy awarded her the label, “the greatest poetess I have come across lately” (Hardy 113). Among Mew’s other admirers were H.D., Siegfried Sassoon, and Ezra Pound, who commended her inclusion in Twentieth Century Poetry in a letter to Monro.

Despite critical acclaim, Mew had little money in later life. In recognition of her talent, she was given a pension of £75 per year by Hardy, John Masefield, and Walter de la Mare, beginning in 1924. However, following the deaths of her mother in 1923 and her sister in 1927, Mew grew increasingly distressed and took up residence in a nursing home on Beaumont Street, London, where she lived for just a year. On March 24, 1928, Mew took her own life.

The emotional turmoil suggested by Mew’s final years appears to have been a lifelong burden, as many of her poems bear the mark of “a locus of conflict and psychic pain” (Schenck 318) with regard to her sexuality as well as the mental illness and frequent deaths that plagued her family, though Alida Monro insisted that “It must not be thought […] that [Mew] was always in a state of depression” (Monro x). Her oeuvre manifests a tension between a measured, formal approach to poetic structure and an undeniably radical approach to content—Mew’s poems are rife with feminist political analyses and homo- and autoerotic imagery. Though many critics refrain from categorizing Mew’s poetry as modernist, marked as it was by a conventional approach to form, Celeste M. Schenck argues that “canonized ‘Modernism’ often masks a deeply conservative politics” (Schenck 317), whereas Mew’s traditional style belies a progressive feminist agenda. In its inclusion of content as radical as any canonized modernist’s form, Mew’s work thus urges the renunciation of “any hope for a unitary, totalizing theory of female poetic modernism” (Schenck 317) by unsettling prevailing notions of what the movement we now recognize as modernism entailed.

Works Cited

Bristow, Joseph. "Charlotte Mew's Aftereffects." Modernism/Modernity, vol. 16, no. 2, 2009, pp. 255-280, Project MUSE.

“Charlotte Mew.” Poetry Foundation.

Dowson, Jane, and Alice Entwistle. A History of Twentieth-Century British Women’s Poetry. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Fitzgerald, Penelope. Charlotte Mew and Her Friends. Collins, 1984.

Fitzgerald, Penelope. “Lotti’s Leap.” London Review of Books, vol. 4, no. 12, 1982, pp. 15-16,

Fitzgerald, Penelope. “Mew, Charlotte Mary.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 24 May 2008.

Grant, Joy. Harold Monro and the Poetry Bookshop. Routledge, 1967.

Hardy, Thomas. “To J. C. Squire.” The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, edited by Richard Little Purdy and Michael Millgate, vol. 6, Clarendon Press, 1987, pp. 113.

Mew, Charlotte Mary. Collected Poems of Charlotte Mew. Macmillan, 1953.

Monro, Alida. ‘Charlotte Mew—A Memoir.’ Collected Poems of Charlotte Mew. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd, 1953: vii-xx.

Moore, Virginia. Distinguished Women Writers. E.P. Dutton, 1934.

Schenck, Celeste M. “Charlotte Mew (1870-1928).” The Gender of Modernism: A Critical Anthology, edited by Bonnie Kime Scott, Indiana University Press, 1990, pp. 316-322.

Smith, James. “Mew, Charlotte.” British Women Writers: A Critical Reference Guide, edited by Janet Todd, Continuum, 1989, pp. 462-464.

Woolf, Virginia. “To R.C. Trevelyan.” The Letters of Virginia Woolf, edited by Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann, vol. 2, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978, pp. 419.

Bibliography

Bibliography

The Farmer’s Bride. London, Poetry Bookshop, 1916.

Saturday Market. London, Poetry Bookshop, 1921.

The Rambling Sailor. Edited by Alida Monro, London, Poetry Bookshop, 1929.

Collected Poems of Charlotte Mew. Edited by Alida Monro, London, Gerald Duckworth & Co., 1953.

Collected Poems and Prose. Manchester, Carcanet Press in association with Virago, 1981.

Collected Poems and Selected Prose. Edited by Val Warner. Manchester, Carcanet Press, 1997.

Selected Poems. Edited by Ian Hamilton. London, Bloomsbury, 1999.

Complete Poems. Edited by John Newton. London, Penguin, 2000.

Archival Holdings

The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts: http://archives.nypl.org/brg/19251.

The British Library

State University of New York, Buffalo

F.B. Adams Collection (private)