J. M. Dent

J. M. Dent

Business Type:

Owned By:

Description

Authored By: Lise Jaillant

Joseph Malaby Dent (1849-1926) is best remembered today for the cheap series of reprints he launched in 1906, Everyman’s Library. As Jonathan Rose puts it, “it was not the first attempt at a cheap uniform edition of the ‘great books,’ but no similar series except Penguin Books has ever exceeded it in scope, and none without exception has ever matched the high production standards of the early Everyman volumes.” Dent was the tenth child of a Darlington house-painter. He left school at the age of thirteen and developed a love of literature largely through self-education. After briefly working as a printer’s apprentice he switched to bookbinding, and in 1867, at the age of eighteen, he moved to London where he opened his own bookbinding shop. Dent’s admiration for fine craftsmanship would later influence his decision to market inexpensive books in a distinguished physical format.

In 1888, he founded a publishing firm, J.M. Dent and Company, at 69 Great Eastern Street. Dent’s experience of autodidact culture made him aware of the demand for reliable texts in cheap editions. In 1894, he launched the successful Temple Shakespeare series priced at only one shilling a volume.

Encouraged by this success, Dent went on to launch other series – including the Temple Dramatists and the Temple Classics in 1896, and the Mediaeval Towns Series in 1898. He also worked with contemporary writers (including Maurice Hewlett and H. G. Wells) and artists: The Birth Life and Acts of King Arthur, illustrated by the little-known Aubrey Beardsley, appeared in 1893-1894.

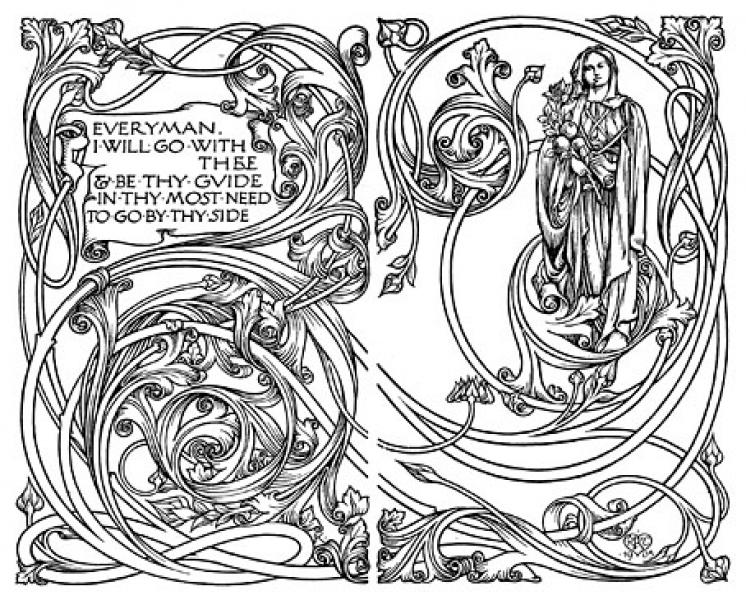

In 1904, Dent started planning a new series of cheap books – Everyman’s Library. As he later explained, his models were “the French ‘Bibliothèque Nationale,’ or the great ‘Réclam’ collection produced in Leipzig, of which you could buy a volume for a few pence” (The House of Dent, 123). In Britain, cheap series of reprints were rarely well-produced (with the exception of the World’s Classics created by Grant Richards in 1901 and acquired by Oxford University Press [OUP] in 1905). The scope of Everyman’s Library was another major difference with its competitors: a total of 152 titles appeared in 1906, under the editorship of Ernest Rhys. “Dent is making a great splash with his series,” wrote Henry Frowde (the manager of OUP’s London business), “and the specimens which I have seen are certainly deserving of success” (Frowde to Watts-Dunton, 30 Jan. 1906). In a 1907 report on the World’s Classics, Frowde remarked: “the success of the venture has, no doubt, been to some extent affected by the gigantic proportions of Everyman’s Library which Mr. Dent has since issued” (Frowde to Cannan, 27 Nov. 1907).

The success of Everyman’s Library depended on the availability of non-copyright books, and the Copyright Act of 1911 (which extended protection to fifty years after the author’s death) was a serious, but non-fatal, blow. The series also survived the difficult conditions of the First World War, including shortage of staff and paper.

Unlike the Modern Library in the United States, Everyman’s Library shied away from controversial fiction. Modernist texts did not join the series until the 1930s (Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse appeared in 1938 for example).

Everyman’s Library was sold in Britain, but also in the United States. In 1928, twenty-two years after the launch of the series, an advertisement in the Saturday Review of Literature gave “six reasons for its indispensability to readers”: (1) its scope (812 volumes, and 23,000,000 copies sold) (2) careful editing and introductions by well-known authors (3) a wide range of texts, with 13 classified departments (including fiction, the largest department with 250 volumes) (4) value for money (many volumes had more than 400 pages) (5) distinguished physical format with quality paper, binding and type (6) availability to a wide range of readers (“here are books that fit the Hand, the Mind, the Mood and the Purse of EVERYMAN”).

J. M. Dent died in 1926 and the business was taken over by his sons Hugh and Jack, and Jack’s son F. J. Martin Dent. Everyman’s Library continued to be edited by Ernest Rhys until his death in 1946. It influenced many other successful series of reprints, on both sides of the Atlantic.

Bibliography and Selected Further Reading

Advertisement for Everyman’s Library. Saturday Review of Literature 21 April 1928: 799.

Dent, J. M., and Hugh R. Dent. The House of Dent, 1888-1938. London: Dent, 1938. Print.

---. The Memoirs of J.M. Dent, 1849-1926. London: Dent, 1928. Print.

Frowde, Henry. Letter to Theodore Watts-Dunton, 30 Jan. 1906. Letterbooks of Henry Frowde. Oxford University Press Archive.

---. Letter to Charles Cannan, 27 Nov. 1907. Letterbooks of Henry Frowde. Oxford University Press Archive.

Hoppé, A. J. A Talk on Everyman’s Library. London: Dent, 1938. Print.

Rhys, Ernest. Everyman Remembers. London: Dent, 1931. Print.

---. Wales England Wed. London: Dent, 1940. Print.

Roberts, J. Kimberley. Ernest Rhys. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1983. Print.

Rose, Jonathan. “J. M. Dent and Sons; J. M. Dent and Company.” British Literary Publishing Houses, 1881-1965. Ed. Jonathan Rose and Patricia Anderson. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 112. Detroit: Gale Research, 1991. LiteratureResource Center. Web. 30 Dec. 2015.

---. The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2001. Print.

Ross, Donald Armstrong, ed. The Reader’s Guide to Everyman’s Library. London: Dent, 1976. Print.

Thornton, James. A Tour of the Temple Press. London: Dent, 1935. Print.

Archives and Papers

J. M. Dent & Sons Records, 1834-1986, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

http://www2.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/j/J.M.Dent_and_Sons.html

Business correspondence with Charles Sarolea, University of Edinburgh Library

http://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/307